Weekly Bubbles 5|25

Book Review: An American Girl Anthology

Something monumental happened in my life this week - a new book containing a collection of essays on American Girl dolls became available to purchase online. I bought, paid for rush shipping, and immediately dove back into the world that defined my early childhood.

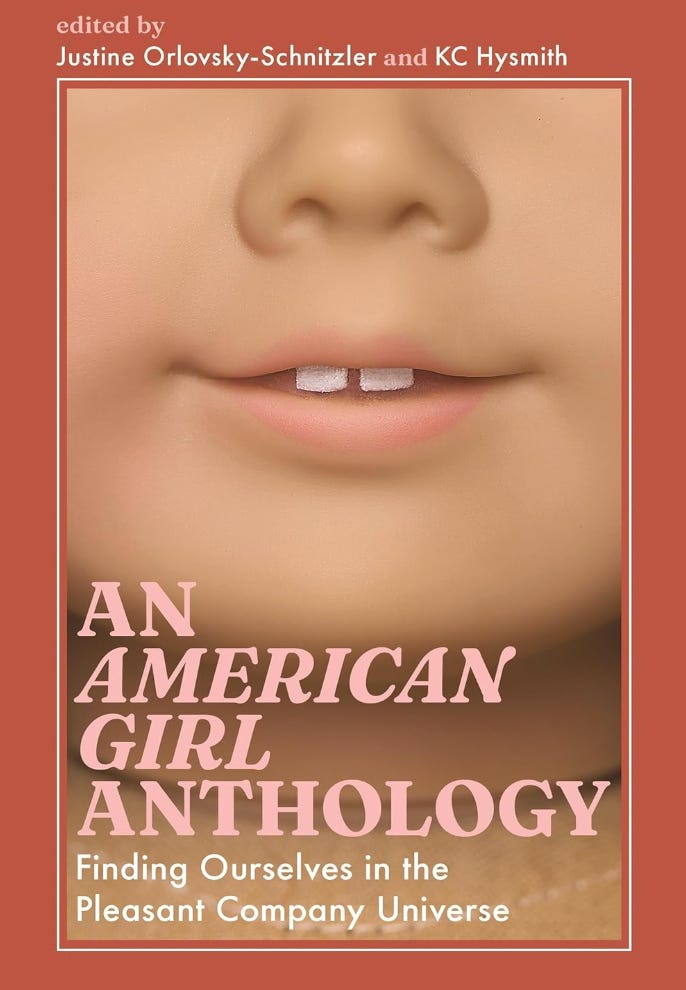

An American Girl Anthology: Finding Ourselves in the Pleasant Company Universe, edited by Justine Orlovsky-Schnitzler and KC Hysmith, is a thought-provoking collection of essays that delves into the cultural and social impact of the American Girl franchise. The anthology features contributions from a diverse group of scholars and writers who examine how American Girl dolls and their accompanying narratives have influenced generations of consumers. The essays explore topics such as the representation of race and class, the role of nostalgia, and the complexities of consumer culture.

One of the essays even mentions my Feminism professor at USC, Sarah Benet-Weiser - shout out my queen!!!

Caveating that I haven’t finished the book entirely yet, I found a lot of it echoing the liberal need for perfection I discussed back in my book review of Wright Thompson’s The Barn. There are moments where the brand unequivocally made poor choices, but reading the anthology made me question if this need for perfection is throwing the baby out with the bathwater. Are we really going to pick apart all of American Girl’s missteps across 40 years through a 2025 lens and dismiss the quiet good its toys’ messaging has done all these years?

Falling Short

Any book, brand, article, person, etc that tries to take on explaining the American experience (much less to 8 year olds) gets some things wrong and could’ve done better on others. American Girl is not immune. So, without further ado, here is my unofficial list of things we can be mad at American Girl for doing. This is also my caveat that I understand there are problematic things within the brand, even though I argue American Girl is overall positive to society.

Using white authors for Addy’s, Josefina’s, and Kaya’s book series.

Waiting until far into the 2010s to create a disabled historical doll (Maryellen), but making her story reference March of Dimes, which at the time the doll is set in the 1950s was the organization to assist in spreading the polio vaccine, but today in 2025, dabbles in the pro-life (AKA pro-birth, anti-women) movement.

Using the Josefina face mold for Nellie (an Irish immigrant) and Rebecca (a Jewish immigrant) - or in other words, “othering” any dolls not considered to be a WASP.

Debating Addy’s release over worry she wouldn’t sell (PUH-LEASE!).

Starting the brand with three dolls (Samantha, Molly, and Kirsten) who are all white.

Not building out Ivy Ling’s story further to include the political activism of Asian Americans in San Francisco throughout history, but specifically in the 70s.

Not having a main historical character who is Asian-American. Ivy is only Julie’s friend, not the main character.

Only having one Asian-American “Girl of the Year” who was released during Covid and who’s story includes references to the “kung-flu” when the doll learns about racism in the plot line.

Briefly discontinuing many of the original historical characters, including most of the minorities (Addy, Josefina).

Removing many of the accessories from historical figures, including Addy and Josefina.

Renaming Rebecca’s Shabbat candles to generic candles online and in the catalogue.

Waiting until 2009 to release a non-Christian historical doll.

Waiting until 2017 to release a Hawaiian historical doll.

Not acknowledging that Marcus is a slave in Meet Felicity.

Until recently, the only long-running Black American Girl doll was a slave (Addy).

Not acknowledging the civil rights era until 2016 with the release of Melody.

Bitty Baby arguably reinforcing gender roles.

American Girl didn’t have a ton of choices for the lookalikes until the last 5-10 years.

Choices in Capitalism

One thing this book largely ignores is that American Girl doesn’t just pull the historical dolls and their accompanying books out of their ass. The brand actually invests thousands of dollars in pulling together a committee of historians, community leaders, and more to advise on the doll the brand is looking to create. For example, to create Melody, the brand’s only African American doll since Addy (with the exception of Cécile Rey’s three yea run, the brand utilized a Black author (thank God) and consulted with a 6-person advisory board including: civil rights activist Julian Bond, former Detroit City Councilwoman JoAnn Watson, and Juanita Moore, the president and CEO of the Charles W. Wright Museum.

American Girl has consistently used the best experts available at the time to create both the historical dolls and their worlds to paint an age appropriate, but mostly honest, snapshot of a time in American history. Of course, this comes with a big fat BUT - that American Girl does still exist in a capitalist society. The Dolls of Our Lives podcast, run by two historians and runs through each book series for each historical doll, discusses how the brand spent painstaking hours agonizing over whether Addy should be a slave that breaks free or if the doll should be set in other times, like say, the civil rights movement. According to research done by the podcast hosts, the experts and community leaders on Addy’s 6-person board advised that not only should she be a slave breaking into freedom, she has to be. Jury is still out on that decision, but it shows both the care the brand takes in releasing historical figures and the knowing that the brand exists in a political gray area. In other words, it wants to make money, do some good, and not piss anyone off too badly in the process - or at the very least, not create irreparable damage to the brand. That is a fine line to walk, especially as the years have gone on.

One contributor to the book goes so far to point out that the capitalist needs are antithetical to the narratives the brand is selling in civic service, caring for others, finding yourself, etc. I’m not saying this point doesn’t have merit, but the reality is for the brand to do ANY good, it has to remain profitable. If the dolls disappear, so does a lot of young girls’ (and boys!) first introduction into American history. So does the seed the historical figures’ stories plant that grows into an understanding of independence and its cruciality in cultivating a more equal world. As I said in my lengthy discussion of The Barn, the problem with the liberal leaners is that it is never good enough to do more good than bad. Perfection or nothing - and quite frankly, that isn’t how change is made.

And, these business and brand reputation decisions are not made in a vacuum, but rather they are made at the exact moment in time they are happening. A lot of the contributors in this book largely ignore the time and place the older historical dolls were released. In 2025, it seems unthinkable for a brand to only have one Black doll and render young Black girls to have to envision themselves as slaves where the white girls are baking blueberries in Samantha’s kitchen in a mansion in 1907. And, it both is unthinkable and should be. But, that wasn’t the case in the early 1990s. And so then do we just not have Addy at all because it isn’t the perfect story? Do we forgo teaching the horrors of slavery in a digestable way for young readers completely? I think that would also be unthinkable. A decision for Josefina in 1997 is very different from a decision for Kaya in 2002 or Nanea in 2017 - likewise for Addy in 1993 and Melody in 2016. The Pleasant Company started with three dolls in 1986. Choosing which “American Girls” to start with in 1986 is a very different decision than if it was made today in 2025. The brand has needed to be able to sell dolls in the current climate of the time. Given where American society has fallen on various issues from race to class to ethnicity to economics has changed drastically over the last 40 years. I think it is fair to say that while the brand has been far from perfect, it has also done a good job of balancing selling dolls for a profit and gently nudging society in an open, civic-minded direction.

For proof of this, just look at the Millennials. We are the first generation to play with American Girl dolls and we are also the first generation of women to overwhelmingly live on our own, start businesses, and run for office. There are more women in college and law school than men right now. We’re in therapy. We’re empathetic, but we also live with ourselves at the center of our lives - not men, not family wishes, not gender stereotypes and roles foisted on us by society - but ourselves. The Millennial women overwhelmingly voted against Donald Trump three times over. What do many of us have in common? We are the American Girl generation. We read each book series and ate up the repetitive story pattern of independence, coming of age, learning about the world, and ultimately, trying to make the world a better place. Where Barbie made us dreamers and painted for us all the different things we could aspire to do beyond secretary or mother, American Girl centered the narrative around us and told us you can be a force to be reckoned with, even at 8 years old. And, we, as a generation, largely answered the call. And, American Girl managed to make money through all that!

An Imperfect Teaching Tool

As a Mexican-American, Native American, and first generation Italian immigrant (give me something more melting pot American than that mix - I’ll wait…), I feel I have every right to critique American Girl on choices where they fell short. Although An American Girl Anthology is largely a love letter to a toy brand that set us down our individual paths in life, almost every contributor has some - to varying degrees of rational - bone to pick with what the brand missed on. I’ve always been a little miffed that white authors wrote Josefina and Kaya’s book series, but I largely found myself defending the brand while reading each contribution.

I sat with this conundrum all week as I tried to figure out why I felt so ferociously that the brand is largely a force for good. I ran through the obvious, teaching that everyone is an American Girl, teaching girls to be brave and independent, teaching us all to be the change. But, when I dug deeper, I realized it is because the brand gave me a vocabulary and an ability to have a dialogue about my heritage.

My first American Girl doll was a Bitty Baby given to me by my maternal grandparents on Valentine’s Day in 2001. Bitty Baby, like the lookalike dolls, comes in various skin tones, hair colors, and eye colors. My grandparents picked the hispanic skin tone Bitty Baby to bequeath their only grandchild. This was the first time in my life anyone acknowledged to me that I was a Latina. Even my birth certificate lists my mom’s ethnicity as “Spanish” (eye roll at Connecticut’s race option list back in 1996 - I see you nutmeggers). I’ve never asked either of my grandparents or my mom why they chose that, but it had to have been deliberate. I imagine it was a conversation my maternal line wanted to have with each other but couldn’t find the words. Maybe the words were too triggering. Either way, the doll became a conduit to talking about heritage.

And, it didn’t end there with a brown Bitty Baby. The highlight of my year from ages 4-11 was the arrival of the American Girl catalogue. If I’m being honest, it still is - my mom is still on their distribution list and we leaf through it together every so many years. My mom would let me circle what I wanted in the catalogue and then would compile it into a list that went out to the grandparents and “Santa” every year. I got to pick my first historical doll around the First Grade and of all the options, I chose Kit Kitteridge - the doll set in the Great Depression. What a foreshadowing for life as a millennial…LOL. I unwrapped Kit that Christmas, beaming to my dad holding a massive camcorder over his shoulder. But, more importantly, the following birthdays and Christmases yielded Josefina and Kaya. I remember asking for Kaya, but I honestly don’t remember asking for Josefina. Additionally, I had a ton of accessories for my lookalike doll (named Hailey) and the “Girl of the Year” dolls, but I didn’t actually have the accessories for most of the historical dolls I owned. The only accessories I had were from Josefina or Kaya’s collections. I specifically remember my mom talking to me about how Josefina is from where we’re from - New Mexico.

Again, I’ve never asked my parents or my grandparents if these were deliberate choices or it was just what I circled that year in the catalogue. Regardless, I’ve come to realize that American Girl gave my mixed family a conduit to speak about ourselves through. Where histories and words may have been forgotten or erased, the dolls filled in the blanks. No one ever said to my face that I’m Mexican - but I figured it out, yes, by family trips to NM, but also, and maybe more significantly, through the discussions surrounding the American Girl dolls.

The dolls were also a positive way to discuss race. The girls in the books weren’t necessarily dealt the greatest hands, but they were fierce, independent, and largely, celebrated. My racial ambiguity wasn’t taught to me in a negative way. I was cool like Josefina. I had a different doll than everyone else with boring Samantha! I actually shared history with one of the American Girls! And, more importantly, I knew which Bitty Baby was mine at playdates.

My rumination continued throughout the week as my view shifted from looking back to looking towards the future. One essay in the book covers Rebecca, who is American Girl’s first Jewish historical doll. Her story is also representative of every immigrant’s story - coming to America, living multi-generationally, and how assimilation occurs differently for each generation of the immigrant family. Rebecca was released in 2009 when I was 13 and aged out of the dolls. But, I realized in reading bits and pieces about her book story - her grandparents refusing to assimilate, while she becomes more and more American, Rebecca being embarrassed at first when her cousin who just arrived in the States speaks with an accent at school, and being ostracized for not being a WASP by her teacher - I realized she operated sort of like My Big Fat Greek Wedding. In some ways, it matters that she is Jewish and they are Greek, but in other ways it doesn’t. Any immigrant family can relate to the story - especially mine.

I started thinking about how it has taken me nearly thirty years to begin to unpack and figure out my identity, and how that will be much more complicated for my child, should I have one, one day. I already can be white passing on any given day, with the exception of July 30, where I am peak tan and morph into my Latina alter ego which my friends and I call, “H-Rod.” My boyfriend is Russian and Irish. There is no shot in hell that any child we might have one day turns out remotely resembling hispanic - although I do hope the spicy personality manifests against all odds. And, for someone who was raised steeped in these cultures with influences of Americana - and not the other way around - how will I not only continue to celebrate my heritage, but teach it to the next generation?

American Girl.

I can use Josefina like my mom did and point out pieces of her story that relate to family histories or echo a place we as a family have actually been and my proverbial child has seen with their own 8 year old eyes in New Mexico. I can use Rebecca to paint the hardship and the hope of the immigrants who crossed the ocean to make our lives possible not all that long ago, mixing Rebecca’s story with experiences my dad or other family members have told me about.

And, on the macro level, the dolls can help me teach my children a lesson I feel is imperative: it is just as necessary to see color as it is to celebrate it. I hate when people say, “I don’t see color,” because at its core, not seeing color is racism softened. It erases our stories and experiences. The reality is, we all experience the world differently. I, as a mixed race woman, experience the world vastly differently than my boyfriend, a white man. And, I think it does people of color a disservice to ignore that fact (this is also why I find critical race theory so necessary in curriculum). It minimizes our experiences and gaslights us into thinking those experiences, and thus ourselves, don’t matter. I want my children to be open to everyone and everything, and I want them to be able to hold space that someone - and in their case, literal family members - might experience the world differently than they do just based on their physical appearance.

I personally feel American Girl can help me on this mission, because in my opinion, it has danced this fine line nearly flawlessly for the last 40 years. One contributor in An American Girl Anthology asks, “Who wants a slave doll?” when discussing Addy in the American Girl universe. Obviously, it is completely valid to say it is unfair for Black girls to only be given one option of a historical doll they are supposed to relate to for decades that requires those girls to envision themselves as slaves. When put like that, it is pretty fucked up. But, then again, so is history. And furthermore, isn’t it necessary for us to see the fucked up juxtaposition that Kirsten is traveling in a new place and is largely free to wander whereas Addy is newly freed in a new place (Philadelphia) and still can’t ride the streetcars? Isn’t it necessary for all of us as Americans to grapple with what freedom means and to who?

And also, as I was reading, I found myself asking the question, who is Addy (and Josefina, and Kaya, and Rebecca, and Melody, and Nanea) for? The Dolls of Our Lives podcast hosts, who are white, discuss how they were first introduced to slavery and the fight for freedom through Addy. And, similar to how the community leaders on Addy’s advisory committee said, without Addy as a slave that frees herself, how does a doll like Melody set in the civil rights era fill in those gaps or have the same meaning?

Am I suggesting the diversity isn’t actually for the girls they represent, but for the white people in the white flight suburbs who need their worlds broadened? Maybe. Is that in and of itself centering white people and also fucked up? Yes. Does exposure help society grow, though? Also yes. If I have learned anything as someone with a foot in both worlds, an imperfect win is still a win.

Obviously the brand has committed many missteps, but overall, it slowly introduced the idea to an entire generation that though we all might look different, some of our stories are more harrowing than others, some of who we are is a product of our time, but we are all American Girls. Each one of our individual stories matters and should be heard not only by our demographic, but by every American. American Girl taught - and continues to teach - entire generations of children how to hold space for the good and evil in our history and for the ways in which we each experience the world differently based on those same good and evil pieces of our country.

The brand, for all its faults, has always pedaled an underlying message that you, as a woman, and regardless of your race or ethnicity, have a story that matters. And, you can write it however you want. It is not perfect, but we shouldn’t be looking for perfection in America, we should be looking for progress. The framers didn’t say perfect, they said more perfect. Which to me, means progress that bends the arc of humanity towards justice. American Girl has undeniably contributed to that arc bending towards justice - albeit imperfectly.